The Impress Service

covered every port in Great Britain. Each major port had a captain in charge,

while smaller ports had a lieutenant. These officers were rarely seagoing

men, and often this was the only alternative to being on half pay. The

senior officer was known as the Regulating Officer, and the headquarters

chosen was called the Rendezvous. Having set up the Rendezvous, the Regulating

officer would then hire some of the local hard men as 'gangers', to form

the Press Gang (on land the press gang was rarely formed by sailors).

| Being

one of the gangers was perhaps the only sure fire way of not being pressed.

The Gang was then sent out and roamed the surrounding countryside in search

of suitable recruits.The gang were paid money for travel, 3d per mile for officers

1d for men, and money per man pressed, anything up to 10 shillings. The

scope for corruption was large, many men would bribe their way out of the

gangs clutches, for a prosperous man a £10 bribe to the press gang

was a small price to pay for his continued liberty. |

|

The press was not new at the time of the Napoleonic wars, it

had been in existance in one form or another for centuries, and slowly

certain rules had evolved about the taking of men for service at sea. Merchant

ships provided obvious targets for the press gang and captains would board

merchant ships to take off any men he might want, officers and apprentices

were exempt. Many merchant captains built hideaways for one or two particularly

valuable men to hide in if the press gang came aboard. The rule was that

the captain had to leave enough men on board to 'navigate the ship',

again a phrase open to wide interpretation.

|

An example of a press warrant,

issued to a ships captain in 1809.

|

|

Although the system of impressment seems harsh and arbitrary

to us now, at the time it was accepted if not popular. The civil authorities on shore would often do everything in their power to disrupt the operations of the Press Gang. Many men were pressed into

service, and reading their descriptions we can see that once caught they

usually accepted their fate with equanimity, at least until they had a

chance to escape. The Navy knew that the chances of a man running were highest at the start of his service, desertion rates progressively dropped off up to 18 months in service. After 18 months the desertion rate was very low. If a man deserted his ship an R was put against his name

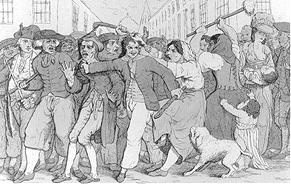

for Run. Avoidance of the Press Gang was a practiced art form and they were unlikely to pick up many men by storming around a town flaming brands in hand. Running battles were frequently fought between the Press Gang and locals, often trying to retrieve a man captured by the Gang. |

A system of prisoner exchange was in operation between Britain and France. The exchange was occasional because the British captured more prisoners than the French. Royal Navy frigates would intercept these ships carrying freed Britons and press as many men as they needed. An unfortunate event for any man looking forward to being reunited with his family. The press gangs in the ports where the ships were returning also kept a look out for them. But the exchange ships were hired merchantmen and the crews were sympathetic to the former prisoners often landing them in places they knew there was no press gang. One ship ran up the river into Rye at night and let 300 men flee into the countryside long before the press gang from Folkestone could catch them.

Officially no foreigner could be pressed into service, although he could volunteer. However if he married a Briton or worked in a British merchant ship for two years, he became liable for pressing. The impressment of Americans was one of the factors that lead to the war of 1812. To protect them the American Government issued Protections, a sort of passport with a general description of the man, to American seamen. However all one had to do to get a Protection was to go before a Notary and swear that he was an American citizen born in such and such state on date whatever. This was not the only objection that the British Government had to Protections, they maintained that any man born British could not change his nationality simply by moving to another country. In an age with no birth certificates and no photographs it was very difficult to prove you were or were'nt a citizen or subject of a particular country, and the Americans had the disadvantage of speaking english so they didn't even sound foreign.

Protections were also issued in Britain, there were several types

ranging from those issued by Trinity House (who controlled pilots) to ones

issued by the Admiralty. Unlike the American protections they had to accurately

describe the man they were issued to. They had to be carried all the time

and produced upon demand. Even these protections were likely to be ignored

at a time of major crisis, known as a hot press, when the Admiralty gave

the order to 'press from all Protections.'

Back to the top

Back to Broadside