Raking Fire

Attacking bow or stern of enemy

|

Raking fire was particularly devastating. Ships of this era were weakest

at the bow and the stern, if an attacking ship could manoeuvre to cross

the enemy in front or behind then they could fire directly down the length

of the ship as the guns came to bear. The round shot bursting through the timbers resulted in a storm of splinters through the deck, in many ways similar to the effect of modern shellfire. Follow this link to see USS Constitution raking HMS Guerriere (opens in a new window). |

In order to rake the enemy it was necessary to sail through

the enemies line. This tactic exposed the lead ship of a column to the

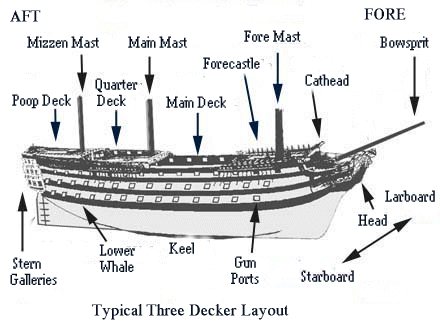

broadside fire of the enemy, so this position was usually taken by a 1st

rate or three decker. The Victory performed this role at Trafalgar,

taking the lead in the Weather column . The Royal Sovereign was at

the head of the Lee column. This was an unorthodox tactic and only the boldest and most confident commanders utillised it .

The orthodox method of attack was in line ahead (hence the term line of battle), both fleets running parallel to each other, and firing broadsides at their opposing number. A few battles were fought like this, but they seldom resulted in a decisive victory for either side, although the casualties could be high.

With the introduction of longer range guns and a change in ship construction

later in the 19th century the tactic was reversed and the commander aimed to

' cross the T ', maximising his firepower at the expense of his opponent.

For the ultimate conclusion to the tactic of crossing the T, and the development of the line of battleship, read about the Battle of Jutland

|

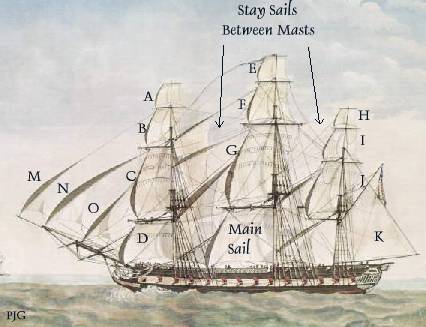

As a general rule the French felt that the best way to disable an enemy ship was to destroy his means of manoeuvering. They therefore concentrated their fire on the masts and rigging, launching their broadsides on the upward roll of their ships. This fire policy often crippled the British ships, preventing them from pressing home their attack, but was less deadly to the crew. |

Although only a very general rule this contrast in tactics goes some way to explaining the difference in casualty figures between the British and enemy sailors. The British

percentage of killed to total casualties was just over 25%, i.e. three

wounded for every one killed. But for the enemy the percentage was 55%,

i.e. for every four wounded five were killed.

The speed with which the guns were loaded and fired by the Royal Navy gun crews was also higher than the French and Spanish, also a factor in the higher casualty figures for the enemy fleets.

The destruction of the enemy ship by gunfire was one of three elements that could lead to death in battle; the other two were fire, and the sea. No British ship was sunk or burnt in any of the great battles, in fact only 8 ships of the line were burnt or blown up throughout the whole war, 17 were wrecked and 3 foundered. The French suffered some major tragedies, such as the Orient at the Battle of The Nile and the Indomitable at Trafalgar, which lost 1250 men from a crew and troops numbering 1400.

When the USS Constitution with a crew of 456 defeated HMS

Guerrierre, crew 302, The Constitution suffered 14 casualties

to the Guerrierre's 78. The American Frigates fired faster and more

accurately than the British thanks to training, the use of a new powder

charge encased in lead not cloth, (no need to swab out the gun),

and gunsights, an innovation not utilised by the British. Till this point the British captains had relied on getting their ships close to the enemies, a tactic that meant rate of fire was more important than accuracy at longer ranges.

The odds were in favour of the larger Amercan ships in the ship

to ship engagements that happened during the War of 1812, but the British

were used to taking on larger opponents and it must have been a shock to

the Admiralty to start losing such engagements so comprehensively.

For a first hand account of an encounter between an American frigate and a British frigate read Samuel Leech's story.

|

|

Click on the link to see "hms" Rose, a modern recreation of a Royal Navy frigate.

Rose

There were 6 boats carried on HMS Victory, 1 launch; 1 barge; 1 pinnace; and 3 cutters.

The Launch, at 34 feet this was the largest boat on board. It was the main working boat for the ship, carrying stores and landing parties. It could be sailed or rowed.

The Barge, 32 feet long, this boat was mainly used to convey the Admiral ashore or to other ships.

The Pinnace, 28 feet long, this boat was mainly used to convey the Captain and the officers ashore or to other ships. It could also be sailed or rowed.

The Cutters ,there were 3 cutters, two of 25 foot in length, the third 18 foot long.

The two 25 foot cutters were kept ready for action, slung out on davits, they could be swiftly lowered, perhaps to retrieve a man who fell overboard, or to turn the ship round if the wind was light and it got stuck in irons as it tacked. The two larger cutters had two masts and the smaller one, they were rowed by six and four men respectively.

|

|

|

A small carronade, of the sort that might be used on a ships boat. |

A ships cutter. Photo reproduced by kind permission of the Historical Maritime Society |